Insights Blog

The 5 Patterns Keeping Good Teams from Getting Unstuck

Even high-performing teams can hit walls when they mistake activity for alignment, underestimate connection needs, or leave decision-making processes unspoken. The key to breakthrough isn't fixing what's broken—it's bringing intention to team culture, communication, and collaboration.

Read Article

The 5 Patterns Keeping Good Teams from Getting Unstuck

Even high-performing teams can hit walls when they mistake activity for alignment, underestimate connection needs, or leave decision-making processes unspoken. The key to breakthrough isn't fixing what's broken—it's bringing intention to team culture, communication, and collaboration.

Read Article

Why Emotional Intelligence is Important in Leadership

Leaders who develop emotional intelligence—the ability to recognize and manage both their own emotions and those of their team members—create more effective, collaborative work environments and spend less time firefighting while building stronger, more productive relationships.

Your Team Isn’t Broken—But Is It Thriving?

Your team might be hitting goals, but are they thriving? Discover a framework to help teams build trust, improve collaboration, and unlock their full potential.

Read Article

NPS vs. eNPS: Understanding the Difference and Why Context Matters More Than the Score

Think your eNPS should match your customer NPS? This common misconception is costing leaders valuable insights into what their employee engagement scores actually mean.

Read Article

What Makes a Great Executive Coaching Program?

While most executive coaching programs focus on conversations, the truly transformative ones are built on five elements that separate real leadership development from expensive talk therapy.

Read Article

5 Biggest Mistakes Companies Make on Culture Surveys (And How to Avoid Them)

Discover the five critical non-survey factors that determine whether your organizational culture assessment will drive meaningful change or become just another corporate ritual.

Read Article

A Leader's Guide to Workplace Assessments

Discover how to select the right workplace assessments to drive better hiring decisions, enhance team effectiveness, and accelerate employee development for measurable business impact.

Read Article

Customer Service Is Not a Department, It's a Leadership Imperative

Customer service is much larger than a department. It's a leadership imperative because every team member impacts the customer experience regardless of role.

Read Article

What is Executive Coaching? A Science-Based Approach to Leadership Development

Unlock your leadership potential through proven executive coaching strategies that help today's top business leaders achieve peak performance, just like professional athletes.

Leadership Development: Investing in People, Not Just Positions

Discover why investing in human-centered leadership development isn't just a corporate strategy, but a vital necessity for creating workplaces where both leaders and their teams can thrive.

Read Article

The People-First Formula for Outstanding Customer Experiences

Discover why treating customers and employees as "human beings first"—not transactions or tools—is the secret to creating memorable customer experiences and lasting loyalty.

Read Article

Get the Most Out of Your Employee Engagement Survey

Transform your employee engagement survey from a measurement tool into a catalyst for meaningful organizational change.

Read Article

Managing Political Differences and Election Anxiety in the Workplace

Learn strategies for managing election anxiety and political differences in the workplace to maintain productivity and team cohesion during politically charged times.

Read Article

Transform Employee Experience Through an Effective Culture Survey

Discover how to craft an effective culture survey for employees that measures true employee experience, focusing on people, purpose, and process to transform your organizational culture into a competitive advantage.

Read Article

The Science Behind a Good Cultural Fit

Here are four critical components to consider when evaluating a potential candidate for culture fit.

Read Article

Succession Planning Template: How to Ensure Your Team is Ready

Explore this succession planning template to learn 9 key elements to build a strong leadership pipeline and secure your organization's future.

Read Article

Unlock the Power of Organizational Culture Surveys: A Guide for HR Leaders

A step-by-step guide for HR leaders on leveraging insights from organizational culture surveys to drive meaningful change in their companies.

Read Article

Using Leadership Assessment Tools for Development

The best leadership assessment tools provide a common language, build self-awareness, and create pathways for feedback and growth.

Read Article

4 Key Elements of a Successful Succession Planning Process

Secure your organization's future and ensure leadership continuity with a successful succession planning process.

Read Article

6 Steps to Effectively Use a Culture Survey

Learn how to effectively use an organizational culture survey, ask the right questions, understand survey results, and implement change.

Read Article

How to Make Better Hires

Here's how to improve your hiring process and increase your confidence in making a good hiring decision by using pre-employment tests.

Read Article

6 Steps to Coach an Underperforming Employee

Here are 6 steps to coach an underperforming employee while showing up as an authentic, committed leader.

Read Article

The Importance of CEO Succession Planning for Business Continuity

Discover why CEO succession planning is crucial for your company's future success and learn practical steps to implement an effective strategy that can boost performance by up to 25%.

Read Article

Humanize Your Hiring Process with Pre-Employment Testing

Hear from Carol O'Neill of BW Packaging and Melinda Bremley, Ph.D., of Chapman & Co. to gain insight into how you can implement pre-employment assessments to humanize your hiring process and increase the effectiveness of your new and promoted leaders.

Read Article

Use Psychology Insights for Better Business Leaders

In this recent episode of the Truly Human Leadership Podcast, Dr. Bremley shares psychology-based insights on using assessment and Ph.D. consultant insights in selection and development, common challenges today's leaders face, and her perspective on the future of AI and leadership.

Read Article

Is the 9-box dead? Identifying Truly Human Potential

Discover why the popular 9-box talent grid may be holding your team back and learn about a revolutionary approach to unlock your employees' true potential.

Read Article

Leadership in Times of Transition

In this episode of the Truly Human Leadership Podcast, Chapman & Co. Senior Partner, David Weller, Ph.D., and Partner, Karen Weller, Ph.D., talk about their experiences as leaders during a time of significant change and transition.

Read Article

Understanding the Foundational Importance of Leadership Principles

Making sure your leaders have the right tools and training will enhance how they use your leadership principles to serve as true leaders to your team members.

Read Article

Remove Bias and Increase Diversity Through a Holistic Hiring Process

With holistic hiring and selection practices, your organization can drastically reduce bias and increase the diversity of backgrounds and skills in your workforce.

Read Article

4 Steps to Coaching and Developing Employees

Follow these 4 simple steps to coaching and developing employees for greater collaboration, trust, and growth within your team.

Read Article

The St. Louis Blues Winning Off the Ice

When your company culture empowers its people to show up authentically and work towards the same goal, winning is a lot more than awards and Stanley Cup rings.

Read Article

How Management Can Build Trust in the Organization

A leader’s ability to build trust in relationships, teams, and throughout the organization has a profound impact on the company.

Read Article

Evaluate Your Customer Experience to Strengthen Customer Loyalty

Chapman & Co. worked with a local St. Louis organization to conduct an in-depth analysis of their customer experience.

Read Article

3 Ways to Ensure Your Feedback Works

We give feedback with the goal that a behavior change occurs and the recipient can do more, do better, or do differently.

Read Article

6 Steps to Building Corporate Culture

Caring for people and being accountable to your business is possible.

Read Article

Learning Agility – Depth vs. Breadth

Learning Agility is a key attribute of having potential, but it is not synonymous with potential. I like to think of Learning Agility as depth versus breadth.

Read Article

Learning Agility – 5 Factors

Learning Agility, or the willingness and ability to learn from one’s experience and then apply that learning to new situations, is a key component of potential and can be accurately defined and measured.

Read Article

How to Build Trust in Any Organization or Team

High performance in organizations and teams occurs when you have all four components of trust. Learn what they are.

Read Article

Characteristics of a Learning Agile Person

According to a recent white paper titled Learning About Learning Agility from Columbia University’s Teachers College, people who are learning agile usually exhibit six characteristics.

Read Article

How to Recognize the People Who Make It Happen

Over the past few years, the way we work has changed dramatically and that change didn't come easily.

Read Article

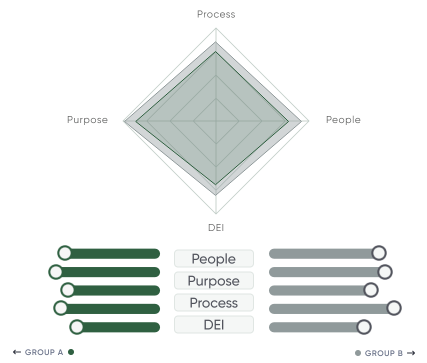

3 Tools to Measure Your Company Culture

Here are three tools to help you measure company culture and build one that becomes your organization's competitive advantage.

Read Article

The Importance of Measuring Organizational Culture

An increasing focus on organizational culture has captured public attention and intrigued the minds of leaders across industries.

Read Article

Someone Shares Their Opinion, Now What?

Explore why one might share an opinion and then explore how to approach opportunities to share opinions with a more inclusive and empathetic mindset.

Read Article